Last night, we had the church hustings in High Wycombe at which I stated that I accept that all the candidates want to achieve the best possible outcomes for everyone. I was glad that this was the message with which the chairman ended the meeting.

Conservatives are committed to a Big Society which works for everyone. Key to reaching this position has been the work of Iain Duncan Smith’s non-partisan Centre for Social Justice. Consider this from Breakdown Britain, which explains the reality behind Labour’s claims – the poorest have been left behind under Labour:

Conservatives are committed to a Big Society which works for everyone. Key to reaching this position has been the work of Iain Duncan Smith’s non-partisan Centre for Social Justice. Consider this from Breakdown Britain, which explains the reality behind Labour’s claims – the poorest have been left behind under Labour:

Poverty is too important an issue to leave to the Labour Party, not least because the current Government’s record is far from being the great success it is presented as.

At the heart of the New Labour narrative on poverty is a promise: Tony’s Blair’s 1999 promise to “end child poverty forever.” But how does the Government define poverty?

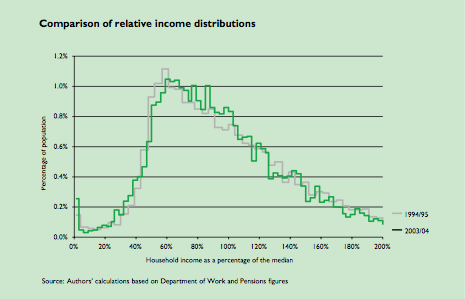

Essentially, it is by means of a poverty line – dividing the country into simple cat- egories of poor and not poor. This threshold is set at 60% of median household income, the median being the point at which half the population earns more and half the population earns less. This is illustrated in the following chart which shows the number of people falling into each £10 band of household income.

Because there are a large number of people clustered around the poverty line a small income boost targeted at households just below this threshold can result in an apparently dramatic fall in the poverty rate.

There is strong evidence that this is exactly what has happened. Using Government figures obtained through the House of Commons Library, the 1994/95 income distribution for families with children was plotted against that for 2003/04. This ten year comparison is shown below:

This demonstrates that in the area around the 60% poverty threshold the income distribution has been shifted forward just enough to put the peak mar- ginally above the threshold instead of just below it. It is another story at the bottom of the scale, where there are more individuals, not fewer, with incomes of 40% or less of the median. Thus while there are fewer people just below the poverty line, there are more people significantly below the poverty line.

Unsurprisingly, the Government has not emphasised the plight of the poor- est of the poor, focusing instead on the overall poverty figures. But even here progress has been exaggerated through careful selection of baselines. Typically a comparison is made with the late-1990s rather than the mid-1990s when poverty rates hit a low point for that decade. Thus ten year comparisons from the mid-1990s show a smaller improvement than that highlighted by the Government.

Another presentational trick has been to use an out- dated absolute measure of poverty to make exaggerated claims of progress. Thus in their 2001 manifesto, Labour boasted of one mil- lion children lifted out of poverty. By 2005, Ministers were claiming two million. In fact, the official 2005 figure was 700,000 but even this conceals the lack of progress in the number of children in the deepest poverty.

The report goes on and I recommend people read it in detail. Labour’s work agenda isn’t working.

In the meantime, Breakthrough Britain explains how to make substantive progress:

In the meantime, Breakthrough Britain explains how to make substantive progress:

These inspirational [grassroots poverty fighters] showed me that things could be much better if politicians learnt from them ‘what worked’ and ‘what didn’t work’. Government action, though filled with good intentions, can often exacerbate existing problems or create new ones. I was reminded that communities need strong families to bind them together and that families were vulnerable to a society that no longer valued the institution of marriage. I was shown by them what happens when family life breaks down and when the only male role model for a boy is the drug dealer or the gang leader. I saw first hand how drug addiction is destroying families and how parental addiction is too often repeat- ed by their children. Too many of our children are growing up in sad communities where failed education is hereditary and worklessness is a way of life.

What so many of these voluntary sector leaders tell me is that it isn’t just about money. The economy has been growing for 14 years yet the bill for social security payments has risen by £35bn in that period, and there are more people claiming disability benefits than ever before. The number of people who are ‘economically inactive’ has risen yet the business community still continues to argue that we need more economic migrants to fill job vacancies. Too many people are unable or unwilling to work, growing frustrated and increasingly detached from the rest of society. We live in an age where human capital is increasingly important and if we are to maintain our economic productivity in the face of global competition then we cannot allow such a large proportion of our country to be left behind. As our Worklessness and Dependency paper powerfully shows, whether you are a single parent or a married couple, the only real way out of poverty for your family is work.

As the fabric of society crumbles at the margins what has been left behind is an underclass, where life is characterised by dependency, addiction, debt and family breakdown. This is an underclass in which a child born into poverty today is more likely to remain in poverty than at any time since the late 1960s. Bob Holman summed it up when he said that the inner city wasn’t a place; it was a state of mind – there is a mentality of entrapment, where aspiration and hope are for other people, who live in another place.

Therefore the challenge for our Policy Group was to harness the wisdom of grassroots poverty fighters in developing solutions “to mend the hole in the social ozone layer”, to use Dick Atkinson’s phrase. In order to do that we defined the five key ‘paths to poverty’ – family breakdown, serious personal debt, drug and alcohol addiction, failed education, worklessness and dependency. All of these ‘paths’ are inter connected and many of those trapped in poverty have experienced more than one of these problems. For example, fam- ily breakdown leads to worse life outcomes for children but debt is a significant driver of family breakdown. Similarly, high levels of failed education con- tribute to worklessness and dependency. To create a lasting solution to poverty we need to tackle all of these ‘paths to poverty’ at the same time.

For too long now, politicians have been content to adopt piecemeal responses to social problems, reacting to deep fractures in society with a short term policy solution. This approach can often have unintended, and negative, consequences. The classic example of this is the operation of the benefits system. In its justified desire to tackle high poverty rates among lone parents with children, the Government has created a system which contains perverse disincentives for couples to officially stay together. This means that couples have effectively been penalised, making it more difficult for couples on benefit to escape poverty. This situation has even led to fraud and recent Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) figures have shown that there are more lone parents claiming benefits in this country than there are lone parents. It is vital to ensure policy solutions to tackle social breakdown are integrated and holistic and, above all, designed to improve long term well being.

I recommend the report.

Poverty fighting is not the exclusive purview of the left. In fact, the left have failed and it is now the turn of those who believe real progress will be made when people have more to do with one another and the government less. This is why social action is at the heart of contemporary Conservatism.