Concerned constituents — including basic rate taxpayers, pensioners and private residential landlords — have written to me about the Government’s proposed changes to Capital Gains Tax (CGT). In this post, I will set out details of the tax, the proposal, the arguments and my position.

Concerned constituents — including basic rate taxpayers, pensioners and private residential landlords — have written to me about the Government’s proposed changes to Capital Gains Tax (CGT). In this post, I will set out details of the tax, the proposal, the arguments and my position.

I conclude that the way to raise CGT revenues is to reduce the rate, ideally to under 10%.

CGT and the proposals

Via HMRC, “Capital Gains Tax is a tax on the profit or gain you make when you sell or ‘dispose of’ an asset.” Presently, there is an Annual Exempt Amount of £10,100 for each individual and £5,050 for most trustees. One pays tax on the excess over that amount at a flat rate of 18%.

There are a number of reliefs, including, for example, Entrepreneur’s Relief:

If you qualify for Entrepreneurs’ Relief, the amount of qualifying gains liable to Capital Gains Tax is reduced by four-ninths, resulting in an effective rate of 10 per cent on all qualifying gains up to £1 million. Claims can be made on more than one occasion up to a £1 million lifetime limit.

The Coalition Agreement says (emphasis mine):

We will increase the personal allowance for income tax to help lower and middle income earners. We will announce in the first Budget a substantial increase in the personal allowance from April 2011, with the benefits focused on those with lower and middle incomes. This will be funded with the money that would have been used to pay for the increase in employee National Insurance thresholds proposed by the Conservative Party, as well as revenues from increases in Capital Gains Tax rates for non-business assets as described below. The increase in employer National Insurance thresholds proposed by the Conservatives will go ahead in order to stop the planned jobs tax.

and

We will seek ways of taxing non-business capital gains at rates similar or close to those applied to income, with generous exemptions for entrepreneurial business activities.

That is, the Coalition plans to transfer wealth from those making non-business capital gains to those on low and middle incomes.

The arguments

At The Telegraph, Ian Cowie says:

Investors with substantial portfolios of property and/or shares who have not protected them in tax shelters – such as trusts, individual savings accounts (ISAs) or pensions – face the daunting possibility that HM Revenue (HMRC) may grab half their gains.

This could destroy many people’s plans to use buy-to-let portfolios or shares accumulated over long periods of time to fund retirement.

At ConservativeHome, Philip Booth, Editorial and Programme Director of the Institute of Economic Affairs, argues that the Conservatives have made a big mistake in accepting Lib Dem proposals for Capital Gains Tax. He says that CGT is seriously misconceived, that it raises little revenue and that it can do much economic harm.

In particular, Booth argues that CGT is a double tax:

But the really pernicious aspect of CGT is that it is generally a double tax. We think of capital gains enriching somebody as if they arise like manna from heaven – and therefore are worthy of being taxed. But investments are valued for the income they produce. The values of investments fluctuate up and down, but investments only go up in value in a sustained way when investors expect them to be more profitable in the long term. Those profits, of course, will be taxed when they are earned.

Furthermore:

It is beginning to dawn on people that one of the reasons for the financial crash was the foolish over-taxation of equity finance that exists in nearly every developed country. It gives incentives to companies to load themselves with debt and create complex financial engineering instruments. It may not have been the main cause of the crash but the instinctive dislike that governments have for “profits” and the way they treat profits in the tax system needs to be reformed. The coalition wishes to move in the opposite direction.

He concludes:

As it is, this proposal to increase capital gains tax is deeply flawed. It is a kick in the teeth for savers; it is a kick in the teeth for those who cannot afford to avoid it; and it is a kick in the teeth for companies that do not load themselves with debt. The effects on the private rented market could be most regrettable. Why anybody should want to bias the tax system further in favour of debt financing in the wake of the financial crash is a mystery to me and why anybody should want to tax savings and investment yet further, as we recover from the lowest savings ratio in history, is completely baffling.

The Adam Smith Institute, has produced a report, which (emphasis mine):

reviews international evidence on the effect of capital gains tax rises on government revenues, finding that tax rises tend to decrease revenues while tax cuts tend to increase them. It suggests that aligning CGT rates with income tax, as the UK government has proposed, would significantly hit revenues and worsen the deficit, as well as discouraging much needed investment. It also refutes the idea that CGT is primarily a tax on the rich, suggesting instead that CGT hikes will hit ordinary families and – in particular – retirees. Finally, the report describes the idea that people can easily shift income to capital gains and thus avoid taxes as a theory in search of some evidence, pointing to numerous countries with high income taxes and low capital gains taxes where this does not seem to be problem.

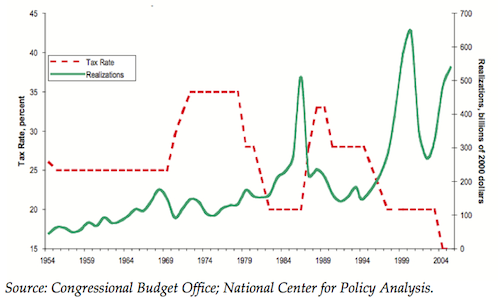

The report includes an illuminating chart which shows that, in the United States, “every time the capital gains tax has been cut, capital gains tax revenues have risen. Every time the capital gains tax has been raised, capital gains tax revenues have fallen.”

The revenue-maximising rate discovered by a study reported in that paper was 9.69%.

The Adam Smith Institute paper concludes:

What then is the correct policy response at the current time? It is clear that the proposal to align Capital Gains Tax with income tax rates, increasing it from 18 percent up to 20, 40 0r 50 percent is inappropriate. It fails to distinguish as it should between short-term speculative gains and long-term asset appreciation. There should be such a distinction, as there is in the US, where gains realized within a year are taxed as income, and longer-term gains are taxed for most people at 15 percent.

The UK could respond similarly, taxing one-year gains at income tax rates, but keeping the 18 percent rate for longer-term appreciation. If the aim were to maximize revenue, that might be achieved by cutting the 18 percent rate to 10 percent. For maximum economic benefit a taper could be introduced to phase it out to zero for assets held for 5 years or more. Either of these policies would be far less damaging than the current proposal.

In his diary, John Redwood MP argues similarly. After suggesting that gains in under one year should be taxed as income, he writes:

I therefore suggest that longer term gains should be taxed at lower rates. If you taxed 2 year gains at 30% and three year gains at 20%, higher rates than the current one, you could tax gains of four years or more at 10%. This should increase the total revenues from CGT by the second year, and offer a stimulus to longer term investment. I would myself go further and offer no capital gains after five years, to send a strong signal to the world’s investors that the UK is back in business as a favourable location.

I have been swamped with support for these suggestions, both from around the country and from Conservative MPs. It would send a strange signal if a Lib/Con government decided to more than double the CGT rate set by a Labour government. It would damage the revenues and be unfair to anyone who saves, is prudent, or who ventures their money for the greater good.

My position

Increasing the tax free allowance for low and middle income earners is an entirely laudable aspiration. I would go further than the LibDem proposal of a £10,000 allowance. It should be possible to buy a modest home, raise a small family and provide comprehensively for their needs without paying income tax at all. The threshold necessary to realise that aspiration is, of course, unrealistic today.

So, how to pay for increases in the income tax allowance? Increases in the rate of CGT can be expected to reduce CGT revenues. CGT is a voluntary tax: it can be avoided by retaining assets. Moreover, something called the Laffer Curve means that beyond a certain point for every tax, increasing its rate reduces revenue because people adjust their behaviour.

Increasing CGT rates would not pay for an increase in income tax allowances: quite the reverse.

If we wish to maximise CGT revenues, then we should learn from the United States’ experience and lower CGT to around 10%, tapering it out altogether for assets held for over five years.

The Coalition Government plans “generous exemptions for entrepreneurial business activities”, but entrepreneurship is the act of bearing uncertainty, so all investment in capital to fund future expenditure is entrepreneurial. Any increase in Capital Gains Tax is a discouragement to entrepreneurship and self-reliance.

There are also arguments to be made about the injustice of sudden changes in taxation and the manner in which they are implemented, but that is a task for another day.

In summary, I am opposed to raising Capital Gains Tax rates because:

- It would reduce CGT revenues.

- It would hit ordinary families and retirees.

- It would discourage self-reliance and personal entrepreneurship.

- It would encourage employment, not entrepreneurship, which we desperately need.

- It would discourage capital formation, which is the essence of rising living standards for ordinary workers.

In a rational world of moderate government spending, we would simplify all taxes and level income tax down towards a new, lower rate of CGT while increasing tax free allowances.

Labour, tragically, has ruled out that option.

See also

My review of Roger Koppl’s Big Players and the Economic Theory of Expectations:

Big Players are privileged actors who disrupt markets. A Big Player has three defining characteristics. He is big in the sense that his actions influence the market under study. He is insensitive to the discipline of profit and loss. He is arbitrary in the sense that his actions depend on discretion rather than any set of rules. Big Players have power and use it.