Having just read Chuka Umunna’s speech yesterday, I am sorry I was not able to make the debate. There is one particular fallacy underlying Labour’s rhetoric and this particular speech’s bluster: government cannot live forever beyond its means.

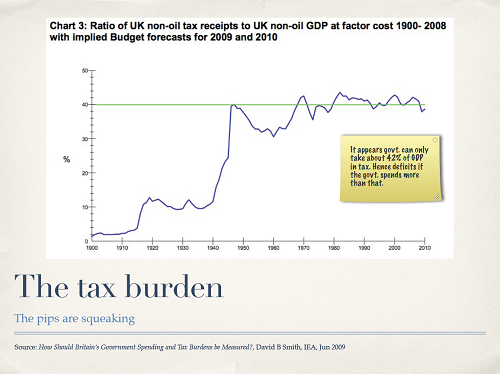

Evidence I have presented elsewhere shows that the total tax burden has been around 42% of GDP for 40 years, whoever has been in power. It looks like there is a practical limit to how much of national income the state can seize. If the state spends over about 40% of GDP for a long time, it must borrow and yet never repay. That this reality was hidden through currency debasement – inflation – for a generation is one of the most important causes of the present crisis.

In Economics in One Lesson, Henry Hazlitt wrote:

The precaution of looking for all the consequences of a given policy to everyone may seem elementary. Doesn’t everybody know, in his personal life, that there are all sorts of indulgences delightful at the moment but disastrous in the end? Doesn’t every little boy know that if he eats enough candy he will get sick? Doesn’t the fellow who gets drunk know that he will wake up next morning with a ghastly stomach and a horrible head? Doesn’t the dipsomaniac know that he is ruining his liver and shortening his life? Doesn’t the Don Juan know that he is letting himself in for every sort of risk, from blackmail to disease? Finally, to bring it to the economic though still personal realm, do not the idler and the spendthrift know, even in the midst of their glorious fling, that they are heading for a future of debt and poverty?

Yet when we enter the field of public economics, these elementary truths are ignored. There are men regarded today as brilliant economists, who deprecate saving and recommend squandering on a national scale as the way of economic salvation; and when anyone points to what the consequences of these policies will be in the long run, they reply flippantly, as might the prodigal son of a warning father: “In the long run we are all dead.” And such shallow wisecracks pass as devastating epigrams and the ripest wisdom.

But the tragedy is that, on the contrary, we are already suffering the long-run consequences of the policies of the remote or recent past. Today is already the tomorrow which the bad economist yesterday urged us to ignore. The long-run consequences of some economic policies may become evident in a few months. Others may not become evident for several years. Still others may not become evident for decades. But in every case those long-run consequences are contained in the policy as surely as the hen was in the egg, the flower in the seed.

From this aspect, therefore, the whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence:

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.

Today is indeed already the tomorrow which the bad economist yesterday urged us to ignore. It’s a pity Labour want us to keep on ignoring it. If their goal isn’t poverty and general immiseration, one wonders what it is.

You can evade reality, but you cannot evade the consequences of reality.